SPARE GODS FROM ‘GAMES’

What we are witnessing today is not religion expressing itself naturally in public life, but being conscripted into political service

SPARE GODS FROM ‘GAMES’

India has never been a country without religion. Nor has it ever been a country dominated by one religion alone. It is, at its core, a civilisation shaped by faiths—plural, layered and lived. It is also a nation of festivals. For centuries, Diwali and Dussehra, Sankranti and Pongal, Ganesh Chaturthi or Ram Navami, Eid and Christmas, Guru Purnima and Buddha Purnima have been celebrated with equal fervour and participation. These were never competitive identities or political markers.

They were shared social moments that bound communities together. Hindus exchanged sweets on Eid, Muslims lit diyas on Diwali, Christians joined Holi celebrations, Sikhs opened langars for everyone. This was not ideological secularism imposed from above. It was organic, lived coexistence.

That India is now under strain

What we are witnessing today is not religion expressing itself naturally in public life, but religion being conscripted into political service—used brazenly as a tool to mobilise votes, silence dissent and manufacture divisions. This shift is not merely unhealthy; it is corrosive. It damages faith, weakens democracy and disturbs the social fabric of a deeply plural nation.

The Constitution of India is unambiguous. There is no place for religious politics—neither in its spirit nor in the Representation of the People Act that governs elections. Secularism, far from being an alien or anti-Hindu concept, was articulated by Mahatma Gandhi and practised by successive governments as a safeguard—protecting religion from the state and the state from religious capture. It was never about hostility towards faith. It was about preserving its dignity.

Yet today, secularism has become a bad word. Those who invoke it are branded “pseudo-secular,” accused of minority appeasement, or portrayed as hostile to Hinduism. The irony is striking: this attack comes from those who practise religious politics most aggressively.

The BJP routinely accuses the Congress—and Rahul Gandhi in particular—of “pseudo-Hinduism.” His temple visits are dismissed as performative, his references to Hindu philosophy mocked as political theatre. At the same time, the Congress accuses the BJP of its own brand of pseudo-Hinduism—one that strips Hinduism of its philosophical depth and reduces it to a permanent election campaign. Both accusations, uncomfortable as they may be, point to a deeper malaise.

Religion has ceased to be a personal moral compass and has become a political credential. Faith is no longer lived quietly; it is performed publicly, audited politically and weaponised electorally.

This is especially tragic in the case of Hinduism, which is not merely a religion in the narrow sense. Hinduism is a way of life, a civilisation, a philosophical tradition that accommodates doubt as easily as devotion, questioning as readily as belief. To reduce it to a narrow religious identity—defined by spectacle, symbolism and slogans—is to betray its essence.

I say this as a Hindu. I was born into the faith and I practise it—comfortably, quietly—at home, in my own way, without spectacle or certification. My Hinduism does not need political endorsement, public display or state protection. It is personal, reflective and rooted in values, not volume. When I say “For God’s sake, spare my Hinduism,” it is precisely because I cherish it. I do not want my faith dragged into election rallies, television studios or gaming consoles. Hinduism, to me, is too profound, too plural and too ancient to be reduced to a campaign slogan.

Hinduism has survived centuries of onslaughts—political, cultural and physical. Empires rose and fell, rulers came and went, yet the civilisation endured because it was never dependent on power for its legitimacy. As a way of life, Hinduism does not require political patronage to sustain itself. It has always drawn strength from its ability to adapt, absorb and regenerate. It will not only survive without political protection; it will flourish on its own. What it does need protection from is trivialisation, appropriation and political exploitation.

The politicisation of the Ram temple inauguration in Ayodhya illustrates this danger. For millions, the temple represented spiritual closure after decades of legal and emotional conflict. It should have been a moment of quiet reverence. Instead, it was allowed to become a political spectacle. Devotion was subtly conflated with endorsement. Participation was framed as loyalty; absence was interpreted as hostility. Faith was not merely celebrated—it was claimed.

Even festivals—once organic expressions of shared culture—are now filtered through political lenses. Which celebrations receive amplification, which are met with silence, and which attract suspicion increasingly depends on political convenience. This is a sharp departure from India’s civilisational reality, where festivals thrived precisely because they were inclusive, not policed.

Religion has also become a convenient diversion from governance failures. Unemployment, price rise, agrarian distress, widening inequality and even law-and-order concerns are frequently pushed aside when cultural flashpoints dominate the discourse. Faith becomes noise. Accountability recedes.

But symbolism has consequences—especially when outrage is selective. Recent reports of 17th-century temples in Varanasi being demolished for the expansion of a funeral ghat should have sparked an uproar. These temples were built by Ahilyabai Holkar, one of the most revered figures in Hindu history. Yet there was barely a murmur from BJP or RSS circles. No sustained television debates. No prime-time panels. No hashtags proclaiming Hinduism under threat. No breathless comparisons with historical destruction. No anchors screaming about civilisational assault and competing to sound the loudest alarm.

Had this occurred under any other government, the reaction would have been ferocious. Studio anchors would have been bouncing on their springboards, shouting about attacks on Hinduism and invoking historical cruelty. Instead, there was a stunning silence. The demolition happened under a so-called double-engine government. Shankaracharyas and several saints had earlier criticised the Uttar Pradesh government for demolishing centuries-old temples in Ayodhya and Varanasi for infrastructure projects. These were not political actors. They were spiritual custodians. Their concerns were conveniently ignored.

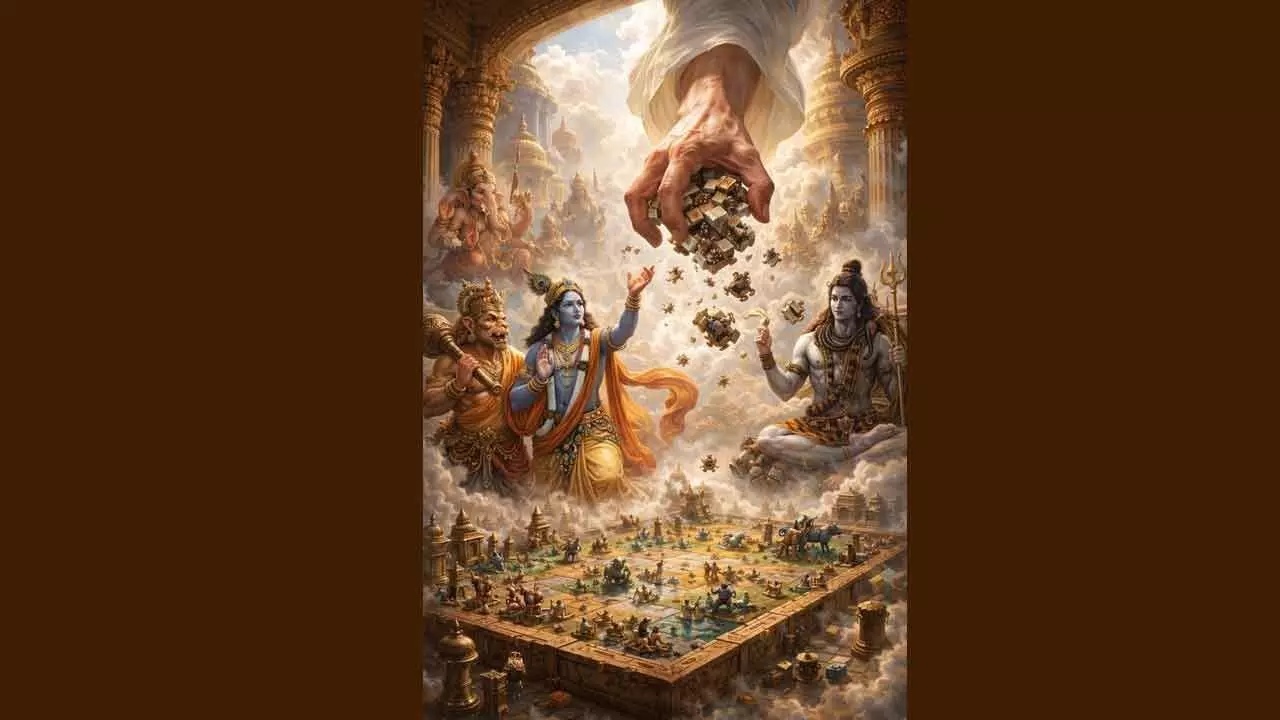

The contradiction deepens further with the Prime Minister’s own words and actions. Narendra Modi has referred to the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as mythology, unsettling many believers who regard them as itihasa—civilisational narratives blending history, ethics and philosophy. At the same time, he has suggested that India should use these very narratives to compete in the global gaming industry, explicitly proposing Hanuman as a gaming character.

Hanuman is not intellectual property. He is a deity worshipped daily by millions. Turning him into a gaming avatar—subject to scoring systems, monetisation and entertainment cycles—raises deeply uncomfortable questions about commodifying faith. One must then ask: where does this end? Imagine the trivialisation of Lord Krishna from the Mahabharata as a gaming character accumulating points, or Lord Ram versus Ravana reduced to levels, leaderboards and bonus scores. What is being presented as innovation is, in reality, reduction.

The discomfort intensified when the Prime Minister was seen flying a ‘Hanuman kite’ at a festival. The image was celebrated by supporters. But the question remains unavoidable: had a Congress leader done the same, would it have been viewed as devotion—or derided as disrespect? India has seen sedition charges invoked for far less.

This is not an argument against religion, celebration or culture. India’s religiosity is authentic, lived and enduring. Nor is this a defence of tokenism by any political leader. It is an argument for restraint and reality.

Religion should inform values, not replace governance. It should inspire compassion, not polarisation. It should remain a shared inheritance, not a political weapon. When parties compete over who is the “real” Hindu, Hinduism itself is diminished—reduced from a civilisation into a political slogan.

Secularism is not anti-faith. It is faith’s strongest ally. Hinduism survived and thrived under a secular republic precisely because it did not need state protection.

India does not need less religion. It needs less religious politics.

If gods become mascots, festivals become political signals, temples become props and belief becomes branding, neither faith nor democracy will emerge unscathed. For God’s sake, spare my Hinduism.

(The columnist is a Mumbai-based author and independent media veteran, running websites and a youtube channel known for his thought-provoking messaging)